In Episode 14, the God Learner podcast returns to its exploration of the Nomad Gods, with David Scott from Chaosium.

News

The “Write Your First Adventure” summer workshop has started, with a RuneQuest course by Nick Brooke.

Pirates of the East Isles is out, with some art and minor spoilers by Ludo.

The Red Deer Saga (incorrectly mentioned as “White Deer”) is now available in print.

Volume 1 of Duckpac was indeed released shortly after our recording, and is now Silver Best Seller!

Dates for Chaosium Con 2023 have been announced. You can read Ludo’s report on this year’s convention.

More current news are available in our newsletter, the Journal of Runic Studies.

Nomad Gods: The Magic Game

David gives a one minute summary of Nomad Gods.

Ludo discusses the availability of the game in print, and we mention the VASSAL virtual tabletop version again.

Trying to talk about Les Dieux Nomades, Jörg is lost in memories, and gets confused about which convention he bought it at. We go into a rabbit hole while trying to find when this game was released — if that sounds boring, you can skip ahead or use the time bookmarks (only supported in good podcast players).

We mention Nick Brooke’s fan translation of the French rules terms on his website, here and here. Nick also created a beautiful printable map with all the features of French map, but with a hex overlay that fits.

David mentions the colourful counters of Les Dieux Nomades, as can be seen on Boardgamegeek.

We talk a bit about the problems when names are translated, failing to recognize the translation, and being out of alphabetic order. Note that Jar-eel the Razoress in French is “Jar-eel la Tranchante”.

Ludo gives a shout-out to the illustrations, before we talk about the rules.

David explains the difference between the counters for Nomad Gods where there is no range factor (for spirits of magician units) but a reflection factor telling whether a counter could attack neighbouring counters in spirit combat using the magic factor or whether it could fight back rather than just soak up damage with the magic factor. But then, there are units with a range factor of zero in Dragon Pass, too, and there are a few spirits that remain on the board and can attack neighbouring hexes with their magic, too, so it is more a case of different terminology than different rules.

David relays what Greg Stafford told him: “It was one of the flaws of the Praxians that they were tied much more to the spirits than they were tied to the deities, the greater gods.”

This focus on spirits and animism is the result of the great destruction from the Gods War in Prax. That’s why each major tribe has a shaman counter, and each shaman has a fetch.

RuneQuest emulates the worship of deities as spirits by giving a chance of contacting a god or goddess when reaching out to the spirits.

David points out that Cults of Prax sort of maps Nomad Gods in that a lot of Nomad Gods is in the structure of Cults of Prax.

There are unpublished descriptions by Greg Stafford about how the tribes move their herds, with a shaman at the front looking into the spirit world to look for the best magical grazing, etc.

Jörg suggests that Praxians are more versatile in rune magic through spirit cults, but again that is described as the flaw of the Praxian access to magic.

Heroquesting to spirit cults delivers lesser boons, while the spirits are more likely to be allies than patrons.

The concept of the fetch as the other side portion of the shaman is introduced here, and carries over into the RuneQuest rules (which were first published a year after Nomad Gods).

We find out more about the social position of shamans, but shamans are described as “crazed and rabid people, more than a little mad from their contact with the gods.” David puts that statement into context with Greg Stafford’s later experiences and practices in shamanism, and blames it on older concepts and misconceptions of 19th century anthropologists about shamanism.

David makes clear that a shaman is someone who is in charge of when they have contact with the spirit world and when not, so while there are times when talking on the invisible iPhone is appropriate, this happens at the shaman’s choosing and not at the spirits’ whim. Somebody constantly beset by spirits is not a shaman, or at least not a successful one.

Ludo mentions Mircea Eliade’s “Techniques of Ecstasy” as a good source on shamanism, a book that is not readable (from cover to cover) because of the learned document containing many examples. It’s considered good to dip in for specific items though.

As a source for shamanism and spiritualism, David recommends Sheila Paine’s “Amulets: a world of secret powers, charms and magic.” Any book on symbology would be good.

Shamans work with the spirits, and spirits have their own agenda, and that may be different from mortal expectation.

We talk about the Soul Winds, a devastating weapon of mass destruction that may cost you your tribal shaman, and that requires alliance with one of the Great Spirits (the Wild Hunter, Malia, or Oakfed). David suggests that this is better suited to the boardgame than to the roleplaying game.

We meet the various categories of spirits of Prax. David points out that most of these have appeared and are going to appear in the new edition of Cults of Glorantha.

I talk about the five elements having something of a balance in Les Dieux Nomades, but not in the original game.

We discuss the Lunar spirits in that game. David points out that there was a list of Lunar spirits in Wyrm’s Footnotes #4, page 49. It’s available in PDF from Chaosium, although might as well get the bundle of all 14 original issues.

The original Nomad Gods counter sheets contained a number of “mystery counters” including those of the Lunar spirits Book of Dale, Twinstars (also in the Dragon Pass boardgame) and the Watchdog of Corflu (one of the pieces which the French illustrator for Les Dieux Nomades got terribly wrong).

David goes through the list, and the discussion lands at the Medicine Bundles of Prax, plunder items useless for an individual but powerful on a clan or tribal level. David goes into what Medicine Bundles are, who would have them, and explains the mutability of their appearance as they fade in and out of existence. A Medicine Bundle embodies magical power, but the objects in the bundle are an embodiment of what it does rather than the actual things.

We arrive at Tada’s Grizly Parts, huge treasure-type artifacts that can be converted into magical units that can be summoned from Tada’s High Tumulus. We speculate about their appearance and size. Tada’s cudgel is a giant club, but Greg also said it was Tada’s penis. The description has a number of double entendres.

In Prax, Malia is a spirit of Darkness rather than of Chaos (although the way the Disease units work is similar to Chaos magic). David associates the three runes of Malia with deadly diseases (Death), minor diseases (Darkness) and plague (Chaos).

The Spirits of Earth are the spirits of the Paps, a family of their own, and presented as subcults of Eiritha in Cults of Prax.

The Horn of Plenty get special mention as one of the Seven Great Magics of Prax.

Then there is the collection of the “Other Spirits”, with a number of unaligned special spirits.

The Horned God is the entity that teaches shamanism and chooses shamans. It is a spirit that doesn’t have a cult. (Jörg’s speculation is that it is the Fetch of Glorantha.) All spirit cults are subcults of the Horned God. If the Horned God provides anything in RuneQuest terms, he provides Discorporation.

We talk about the Bad Man, the Chaos enemy of the Horned God, and the many masks of the Bad Man encountered in shamanic initiation.

Hyena is “an odd creature”, a spirit made by Genert so that his body parts would not fall to Chaos.

Ludo gets enthusiastic about the Three Feathered Rivals.

David talks about the structure of spirit cults in RuneQuest, and talks about the concept of Spirit Societies, and how they would work in RuneQuest. A spirit society is a collection of culturally similar spirit cults. In RQG, there usually is a greater spirit and a number of other spirits belonging to that group. Some are grouped by elemental runes, like they were presented in the boardgame.

Spirit societies are led by a charismatic shaman that doesn’t have to belong to the spirit cult.

A spirit society allows you to have a shared rune point pool for the spirits in the society. The Water Spirit Society would be headed by Zola Fel, and under Zola Fel you would have River Horse, Dew Maid, and Frog Woman. Your first rune point goes to the big spirit, and then you need to spend one rune point to each spirit cult whose magic you want to be able to cast.

The spirit societies are mainly pan-tribal, although each tribe that has a special strength in one rune will have a great portion of that elemental spirit society.

The one extra benefit from joining a spirit society is that you can learn the rune spell of Discorporation when you join a spirit society.

David point out that there is no spirit society of the Spirits of Air because these spirits are part of the Orlanth cult, which is why there is no shared rune point pool for these spirits.

Also there are two groups of spirits of Fire, one being the Burners led by Oakfed, the other the Star Gazers led by Pole Star, a spirit who has two magical places in the Wastes – Pole Star Mountain in the north and Star Crystal Mountain further south.

All spirit cults generally give one rune spell each, rather than the list of rune spells a theist cults give. The spirit cult of Pole Star gives Captain Souls (in the Red Book of Magic).

David points out the difference of Kallyr’s Starbrow ability which is different from the spirit cult, or the Pelorian forms of the cult (Dara Happans, Pentans).

You can read more about David’s take on Spirit Societies on BRP Central.

Spirit societies are all very minor, so minor that people looking from the outside wouldn’t even notice them.

The Daka Fal shaman may well also run the local spirit society. A shaman is not just working with one particular thing, but will also be a member of other spirit cults, and possibly in charge of the (tribally appropriate) spirit society.

We are talking about examples of published RuneQuest shamans. Jörg brings up Blueface as one example of a very powerful shaman, but being a very early example David describes him as rather weird, with several heroquest abilities rather than shamanic abilities. A “Hunter-Brother Dog-Shaman-Priest” who should have a greater range of spirits.

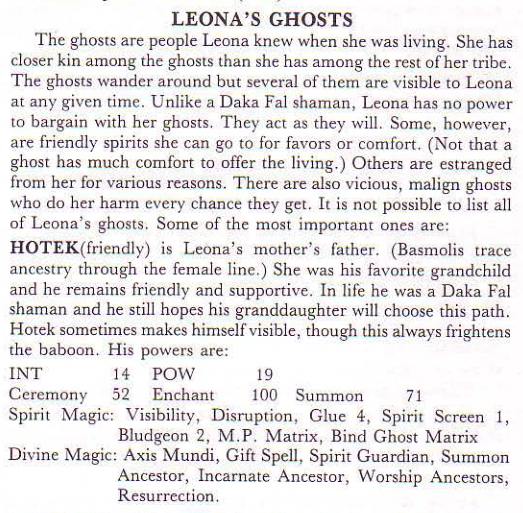

David suggests the example from Heroes Magazine 2.04 (the last issue of that Avalon Hill house magazine). On page 15, the Basmoli shaman Leona has a good backstory. Here is a snippet from Leona’s stat block:

David likes the details of the spirits given, and their origins, like Hotek, the shaman’s mother, and her grandfather as another of her spirits, her dead daughter who was being groomed to become a shaman when she died, and a grandmother who was a shaman.

The one criticism David has with the article is that shamans aren’t loners but strongly bound into their communities.

Leona is slightly insane and not quite a functional shaman because she has lost control over some of her spirits, a damaged shaman.

Ludo asks about the Wild Hunter (Gagarth) and the White Princess (Inora). The White Princess lives in a castle in the middle of the Dead Place, in the Winter Ruins. (Echoes of Elsa are undeniable…)

The Dead Place on the game board map doesn’t much look like anything, but is shown as heart-shaped on more recent maps.

Creatures of Chaos include Thed, Cwim, the broos, and the Pieces of the Devil. Ludo praises the Gene Day illustration of the broos.

David mentions his Q&A on Cwim on the Well of Daliath. Cwim is designed to be attacked by armies rather than by small parties of adventurers. Heroquesters can kill these monsters, but they do it in a different way. Average adventurers can try, and then run.

David talks about seeing Cwim from afar, and changing your route to avoid it. Cwim is the randomizing element that causes the migratory routes of the clans to change. Cwim usually is in the Wastes as the tribes usually ally to keep Cwim out of the sacred land.

Ludo comments on the effects of Chaotic magic in the board game (automatic elimination of an adjacent unit) as “ouch”, which David said sums it up nicely.

We digress to the various types of Gorp presented in River of Cradles. Gorps are “the gelatinous cube of Glorantha”, and are the spawn of Pocharngo, the Chaos god. Various types include “micro-gorp, glue gorp, exploding gorp, regenerating gorp, zoomers (a lot faster than normal gorp), breeders, paralyzing gorp”

We discuss nasty uses for Gorps: Gorp as garbage disposal? Gorp in a bottle labeled as a potion?

The Devil’s Hand is a huge nasty monster. Jörg shows his age when his comparison with the Dreadful Flying Glove from Yellow Submarine was a bit out of context for Ludo, who was listening to metal and progressive rock when he was young.

We return quickly to the Eternal Battle and what lies inside, and possibly beyond.

You can once again see the counters on Boardgamegeek, or in the VASSAL module. The counter sheets serve as art direction.

The magical scenarios serve as training exercises instituted by Jaldon.

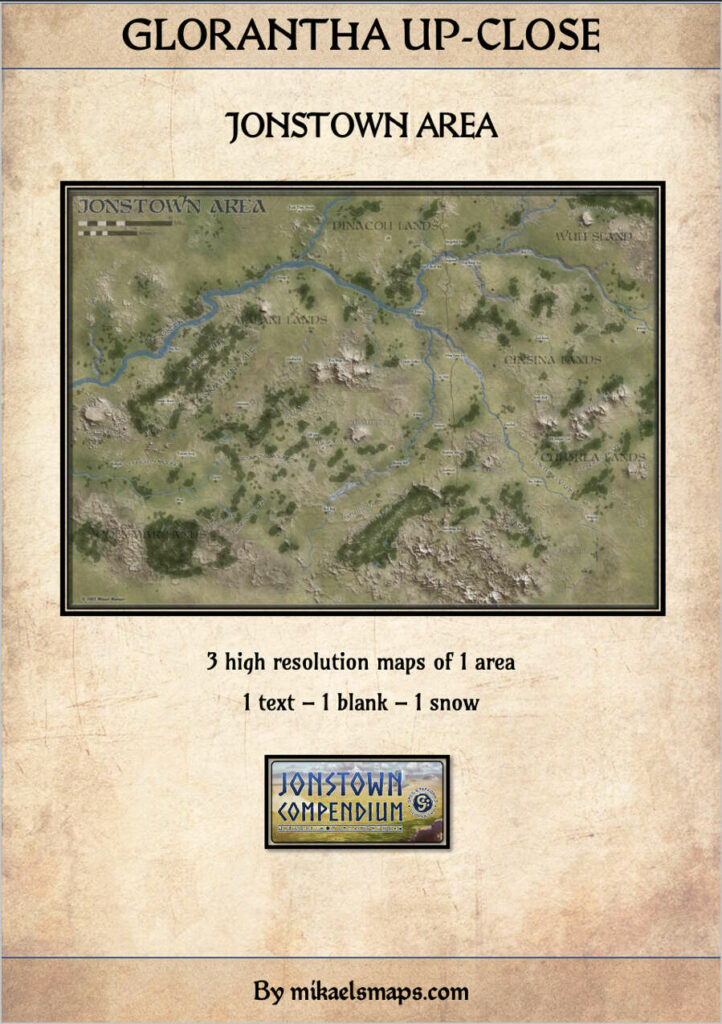

Rather than looking at the text of the prehistory and history of Prax (which admittedly is well known to most players of RuneQuest), Ludo riffs off on the map of the Wastes which is as much (or rather as little) to scale as is the Crater map in White Bear and Red Moon.

Jörg points out that the myth section in the local game of Nomad Gods becomes the world wide foundational myth about the Chaos War. David paints Prax as the final battleground where the last deities perish and descend to Hell to join the Ritual of the Net.

The list of the pieces shows some of the William Church silhouettes at larger scale. David emphasizes the great art pieces by Gene Day which may justify buying the pdf even if the board game doesn’t interest you at all.

David goes into advertising mode, advertising the PDF we’ve been reading for 8.95$.

Jörg vainly wishes for a confrontation between Sor-eel’s Lunar forces and the Praxians, not necessarily at Moonbroth but the march on the Paps and Pavis.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (54.3MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More