Our Guest

Our guest this episode is Simon Phipp, author of Secrets of Dorastor, Secrets of Heroquesting, and author or contributor on many, many other books.

Joerg sadly isn’t present this time: he was stuck on a highway somewhere in Germany waiting for auto-assistance.

Show Notes

Here are some various things we talk about in this episode:

- Getting started playing in Glorantha in 1982… which sounds like 15 years ago but apparently is a lot longer ago

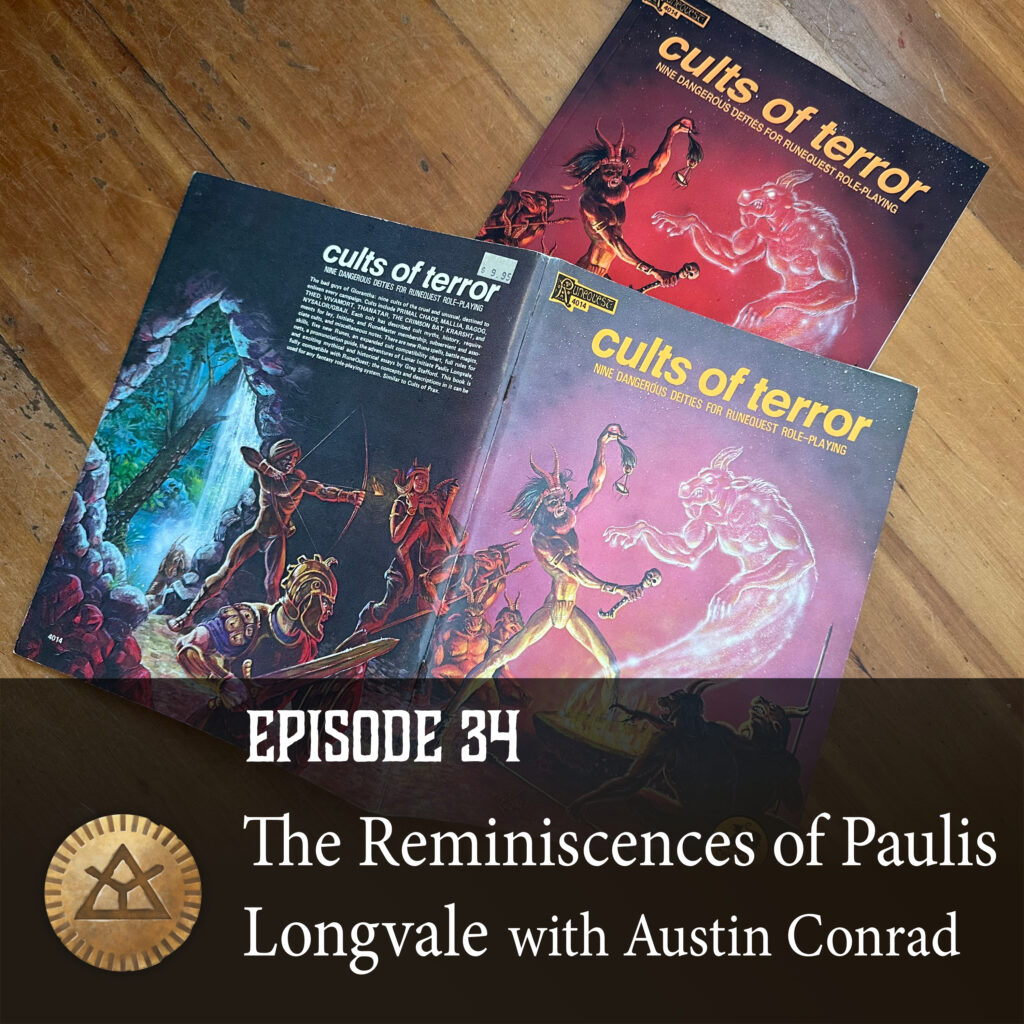

- RuneQuest 2 (with Cults of Prax) was Simon’s first game

- Bud (from Bud’s RPG Review) recently said that it’s like being born with a silver spoon in your mouth

- Watching “World of Sports” and reading “The Iliad” as a kid… as one does

- Simon loves RQ2 for its scale and the visceral feeling you get from playing it

- Playing in Dorastor because it was nasty and unmapped in the early 80s

- The only source was the Paulis Longvale narrative from Cults of Terror

- Other GMs in Simon’s gaming circles were already playing in the “usual places” (Sartar, Prax, Pavis & The Big Rubble)

- We started our series on Paulis Longvale last episode!

- Running a Star Trek-like episodic campaign in and out of Dorastor, starting around 1985

- Later, during the RuneQuest 3 era, Dorastor: Land of Doom was released

- Simon’s players accused him of knowing about the upcoming book’s contents!

- The pros & cons of playing in the vaguely defined Glorantha of the 80s vs the encyclopedic Glorantha of the 2010s

- The Dorastor: Land of Doom’s warning on the back cover is factually accurate… if you consider Simon, as a GM, as a big and ugly thing!

- Come to the Risklands! It’s great!

- The Chaos Nests of Genertela. They’re great too!

- Simon’s Dorastor has multiple Chaos Nests

- In his campaign, Simon’s players killed Razalkark, the king of the Broos, and occupied his fort… and then things got worse

- Chaotic True Dragons are apparently a bad thing?

- Simon tells us the story of Dorastor, including his own interpretation of the whole Nysalor/Gbaji/Arkat thing

- You may remember we discussed some of this with Bud in a previous episode

- Dorastor is filled with lots and lots of bad monsters! How do you get your players to go there?

- Simon’s Dorastor is a bit more nuanced than just “a place to kill monsters”: you can create alliances, do trade, and so on

- Simon gets bored to tears watching the Gloranthan metaplot unfold, with NPCs doing all the cool things

- HeroWars was very guilty of this

- Dorastor is so far away from Dragon Pass that we don’t care what Argrath is doing!

- Simon’s books contain many, many scenarios for Dorastor, plus many adventure seeds

- There are several layers to Dorastor:

- Go in, fight Chaos, come out (if you succeed enough times, become a Dorastor guide!)

- Interact with the big personalities of Dorastor (meet the Spider Queen, she’s great!)

- Storm Bull initiates must learn to prioritize

- Humakti broos! Dorastor ducks! Giant vampires!

- Relationship with the neighbours

- Don’t forget not all cults hate Chaos

- Simon likes messing with his players’ heads

- Chaotic people: they’re not as bad as you think?

- But watch out, you might quickly end up worshipping Thanatar if you don’t pay attention to Simon’s evil schemes

- Finding lost or secret things in Dorastor

- What makes heroes?

- Super-RuneQuest! and other high-level character stats…

- The most useless magic item ever… until it breaks your scenario!

- The problem of long running campaigns

- Acid! Poison! Ash elementals!

- Bathing in gorps!

- Ludo discovers that Cacodemon got Vomit Acid in RuneQuest 3

- Fun with Chaos Features!

- Simon’s best anecdote: basilisks and mirrors!

- Designing encounter locations

- It’s not the GM’s job to know the solutions, it’s their job to setup problems

- Hair and fingernail elementals!

- Illumination in Dorastor: break the rules, become good, become evil?

- Come to Dorastor, it’s lovely, and you can become heroes!

Credits

The intro music is “The Warbird” by Try-Tachion. Other music includes “Cinder and Smoke” and “Skyspeak“, along with audio from the FreeSound library.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (40.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More